How to Know You’re Fully Recovered From an Eating Disorder

Don’t get stuck in quasi-recovery like I did.

Photo by Thomas Kilbride on Unsplash

There were countless times in my eating disorder recovery I didn’t know what was worse: living in the grips of my illness or exhausting so much time, energy, and money trying to overcome it.

After more than a year of outpatient treatment and months of abstinence from restricting, bingeing, and purging my food, I decided I was “healed enough” and stopped scheduling appointments with my therapist, dietitian, and MD.

The next two years looked a little something like this:

Not weighing myself but obsessively mirror-checking to make sure my body wasn’t getting “out of control.”

Not using a fitness tracking device but depending on exercise to compensate or to earn food and alcohol.

Not tracking my calories in MyFitnessPal but tracking calories mentally.

Not abstaining from any foods but often judged myself for what I ate.

Not bingeing or purging regularly but bingeing and purging once every few months “because I earned it.”

The long and the short of it: I cut the recovery cord too soon and ended up working with an eating disorder recovery coach to help me with my unfinished business.

Now, I can confidently say I’m fully recovered. Here’s how I know it’s real this time (and not just my eating disorder playing tricks on me) and how you can gauge where you’re at in your own recovery journey.

A bad body image day is basically equivalent to a bad hair day.

Even though I wholly respect my body, show it daily gratitude, and consider it my most prized possession, once in a while I still catch myself not totally loving what I see when I look at myself.

Sometimes it’s because my clothes are feeling a little snug. Sometimes it’s because I notice a line or “texture” in my skin that I’ve never seen before. Sometimes it’s because things seem wider or stick out farther than usual.

Regardless of the trigger, I’ve trained myself to acknowledge and allow any unpleasant feelings I’m having about my body while also reminding myself that even the most resilient human can’t fully eschew the myriad messages we receive day-in-and-day-out about our “flawed” appearances.

As such, I offer myself a gentle reframe like, “Just like how sometimes you have a bad hair day, sometimes you have a bad body image day,” and I’m back to focusing on things that actually bring my life meaning and joy.

This “brush it off” attitude as a default response to a bad body image day, (rather than internalizing distorted thoughts and feeling tempted to do something about them) can be a key differentiator between someone who’s quasi-recovered and someone who’s fully recovered.

The body (not the unwell mind) dictates what and how much to eat.

Rather than waiting for the clock to hit a certain time or checking my mental calorie tracker to see where I’m at for the day, I simply eat when my body signals to me it wants food.

I nourish myself with adequate amounts of fat, protein, and carbs, and take amounts that instinctually feel right to me rather than measuring or worrying that I took too much of “this” or “that.”

Mind you, it took me a long time to be able to eat intuitively and mute distorted thoughts like, “You know how much fat is in that avocado?” or “Adding more olive oil to your pasta—is that necessary?”

Being able to eat freely based on your individual body’s wants and needs is a clear sign of a healed relationship with food.

Not internalizing food choices.

Allowing yourself to physically eat the types and amounts of foods your body desires is step one, but not tangling yourself up in guilt and shame when you do is very important step two.

If you mentally berate yourself for choosing the cinnamon roll versus the oatmeal, you’re communicating to yourself that you did something wrong, when, in all actuality, you ate a delicious food consumed by hundreds of thousands of people every day.

Likewise, there may be times when you eat past your initial desired comfort level. This is okay. This is you being a human. As long as you feel a sense of awareness—that you don’t feel a loss of control or yourself slipping into a trance-like state—overeating is totally normal to do sometimes.

Having a truly healthy relationship with food doesn’t mean you eat perfectly (that’s not a real thing); it means you don’t cast judgment or hostility toward yourself in the inevitable times you eat imperfectly.

Exercise is a means of caring for (rather than punishing) the body.

We’ve normalized the notion that anytime we eat for fun or pleasure that it indisputably comes with the requirement to “erase” or “make up for” our gluttonous behavior with exercise.

The reality is, this objectionable response is very similar to the self-indictment discussed in the previous point. Like it, you’re sending or reinforcing the message that you did a bad thing, which only further limits you from developing a peaceful relationship with food.

Rather than living by the belief that exercise is a means of burning unnecessary calories you consumed, a recovered person considers it a means of promoting greater health, vitality, and longevity. The line between food and movement is much more narrow, which grants you the ability to eat and exercise more freely.

Read my other piece, How to Navigate Exercise During Eating Disorder Recovery for specific pointers on finding a healthy relationship with movement.

Weight is (nearly) meaningless.

Another sociocultural misstep is how we’ve standardized the scale and kept tabs on our body weight. While I feel such standardization is problematic for the majority of people, it most certainly is for those battling an eating disorder.

I currently have no interest in knowing what I weigh, and my former, super sick self never could have imagined I’d carry such a sentiment. On those rare occasions where I do need to weigh myself (which is essentially only when I need to verify that my check-in bag is within the permissible limit), the number doesn’t phase me.

There may be other examples of how weight does hold some significance, like when someone experiences a sudden spike or drop in weight that could raise concern for a serious health condition at play, or if weight gain or loss is a valid determinant in one’s treatment plan.

But being truly recovered from an eating disorder means you generally honor your body’s wants and needs, which, by default, puts you within your set point range. You don’t need to step onto a deception contraption to dictate how healthy you are or how happy you should be because you’re so attuned to your body that external validation is pointless.

(P.S. You can always request to not be weighed at the doctor’s office. If they refuse your request, you have every right to either walk away and seek care from a HAES provider or turn your back to the scale and ask for them to not read the number aloud and to cover it up on any take-home paperwork).

No more disparaging food, body, or exercise comparisons.

Comparison is human nature. However, when it yields little more than a fractured esteem and an incessant chase for approval, it becomes a weapon of self-destruction.

After I exited eating disorder treatment the first time, I still found myself hyper-concerned with what others were eating, how much they were exercising, what their bodies looked like, and how I stacked up in every stretch of the realm.

If I learned a running mate ran a mile more than I did, I ran farther than normal the next day, despite needing rest.

If someone else didn’t eat dessert, I wouldn’t eat dessert, despite deeply craving it.

If someone else exhibited more toned muscles, I amped up my strength training, despite loathing every second of it.

Being recovered from an eating disorder doesn’t mean you're immune to comparison; it means you’re resilient to letting that comparison control you and trample your self-worth.

No longer negatively reacting to food or body comments.

When I was quasi-recovered, people would say things to me like, “Oh, you look so good!” or “Wow, quite the plate you got there—you must be hungry.” When I heard the first comment, I thought, “Oh no, I’m no longer the skinny one.” When I heard the latter, I ended up leaving part of my food untouched.

Unfortunately, people will forever make unsolicited comments about how your body looks and the food you offer it. You have every right to advocate for yourself in the way that feels right for you, e.g. changing the subject, sarcastically thanking them for their undue observation, or straight up telling them to keep their comments to themself.

In addition to unabashedly standing up for yourself when those unwarranted comments come, a fully recovered person isn’t affected by them (are you seeing a pattern here?). Instead, their body image and the amount of food they intended to eat five minutes prior go unchanged.

Bingeing, purging, or restricting aren’t even a consideration.

Along with continuing to talk myself out of engaging in any binge, purge, or restrictive behaviors, I had a handful of full-on relapses when I was in my pseudo-recovered state.

Not only did I still not have the proper coping mechanisms in place, but the other aforementioned tendencies also made it virtually impossible for me to not have the occasional slip-up.

But now that I’ve overcome all of the underlying, sabotaging behaviors, it doesn’t even cross my mind to binge, purge, or restrict my food. Over the past five years, I’ve had some incredibly traumatic things happen to me, but rather than seeing those moments as an excuse to mistreat my body, I show it extra love and care.

And that’s the difference between someone in quasi-recovery and someone who’s fully healed—you don’t white-knuckle your way through an urge to binge or restrict; you simply don’t have the urge, to begin with.

Final Thoughts

Entering recovery for an illness I wasn’t certain I wanted to surrender was damn hard. Returning to treatment once I accepted I had work left to do was arguably harder.

If you’re in eating disorder treatment or are considering starting or returning, I can attest the investment is worthwhile.

You don’t have to settle with, “This is good enough” or “Full recovery might be possible for others, but it’s not for me.”

Anyone is capable of fully recovering from an eating disorder. Along with my own story, I’ve had the honor of helping so many others form of loving connection with food and their bodies they never thought was possible.

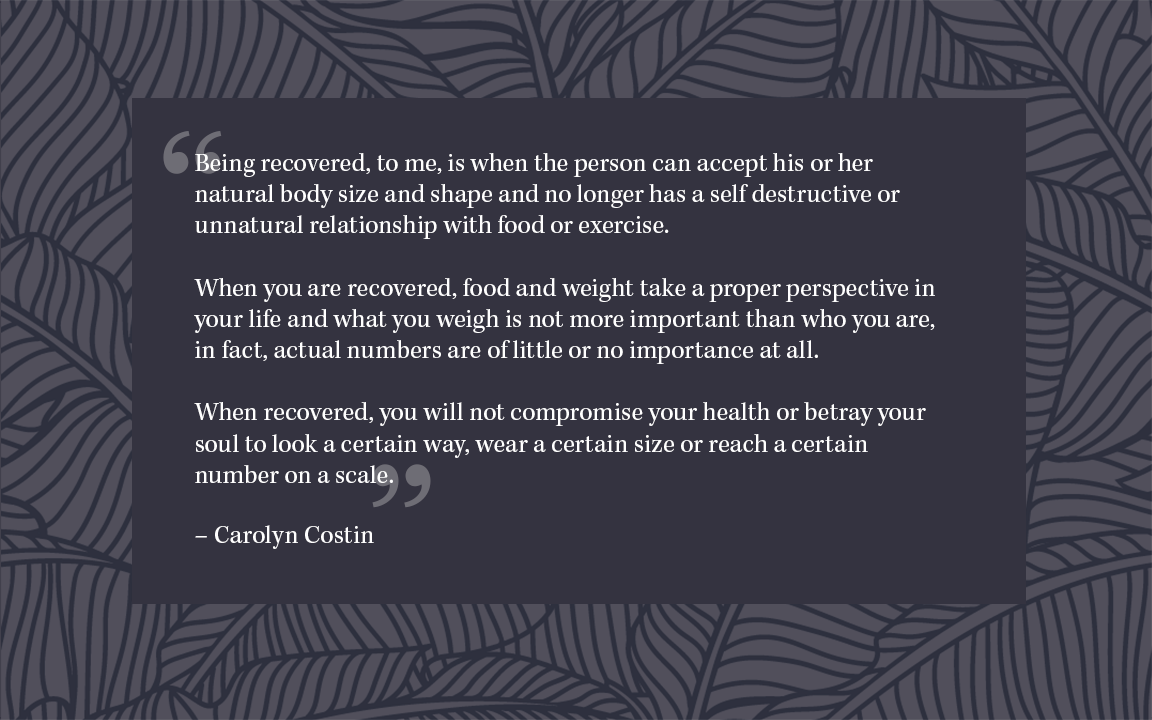

And while there’s no universal understanding of what it means to be fully recovered from an eating disorder, this definition written by eating disorder recovery pioneer Carolyn Costin sums it up rather nicely:

Image created by author.

Someday, you can read this definition, or some variation of it, and confidently say, “This is me.”

Don’t settle for halfway. The view from the mountaintop is waiting for you.